Words presented in a more or less permanent media are what drives our culture and connects us to the recent past and propels us forward. When words are missing, as in prehistoric art, we are not sure of the meanings conveyed by images. We guess and maybe those guesses are correct; maybe not. Words help interpret societies that differ from ours or that have disappeared. We may not get all of the connotations but probably have better interpretations than we would with a non-literate society.

For example, stalagtite/stalagmite pieced circles in Bruniquel Cave in France have recently been dated to 175,000 years ago. Such work had to have religious or cultural meaning for those who built it, but what? We have no written or verbal records.

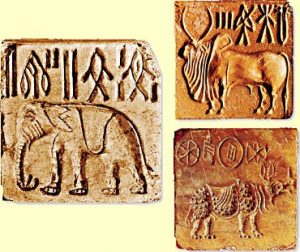

Even much later when there are written records, we may not be able to read them (Harappan and Etruscan). The Pyrgi Tablets, Etruscan gold leafs on the right, hold clues as two of the three are in the Etruscan language and the third is in Phoenecian.

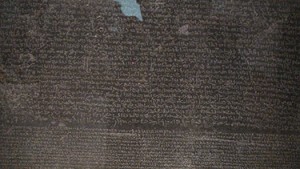

Being able to read written records gives us a huge input to society. That is what the Rosetta Stone did for Egyptian culture and what code breakers have been able to do with other (ancient) languages.

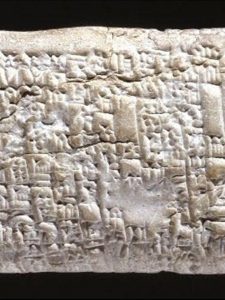

With writing came records that are sometimes surprising. The angry cuneiform letter to a supplier about his inferior goods gives an insight into commercial dealings.

“You have put ingots which were not good before my messenger and said, ‘If you want to take them, take them. If you do not want to take them, go away’. What do you take me for that you treat … me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen, like ourselves, to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you), but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory.

… You alone treat my messenger with contempt! …

You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore my money to me in full.” (Oldest Known Complaint Letter)

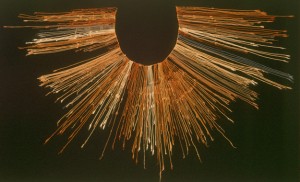

The Incan quipu, very obscure, helped with inventories even though it is knotted, not written, but could not related stories.

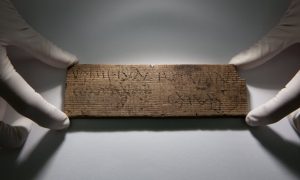

And least likely to have survived, early London records on wood; the earliest dating from 57AD, give some life to early London; those wood fragments were preserved by lying in mud. Originally covered with wax, which has disappeared, the stylus marks made in the wax are, in some cases, readable.

A tablet dated AD 80-90/5, which translated reads: “You will give [this] to Junius the cooper, opposite [the house of] Catullus”. Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images from The Guardian.

A tablet dated AD 80-90/5, which translated reads: “You will give [this] to Junius the cooper, opposite [the house of] Catullus”. Photograph: Daniel Leal-Olivas/AFP/Getty Images from The Guardian.

Oral tradition required exact replication for a message to be understood over generations. It could convey the emotional subtleties not possible in print. With print, it is easier to have “exactness” of words over centuries but the inflection of the oral tradition is lost. There is another path: the video where verbal stories/information can be enhanced by motion. This probably comes closest to showing what is intended.

References:

http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/26/europe/france-neanderthal-cave-circles/

http://www.ancientscripts.com/indus.html

http://www.ancientscripts.com/quipu.html

Thank you Cheryl,

You are always the first. I have been thinking about language, thought and how we think lately to try to understand how a few of us are so different. I know one can live in one’s own head and other will not know what goes on in that head. But it seems too complicated to be explained by differences of words and language.

I hope you did enjoy the course and your new foray into another career so to speak.

Michale